+86-13516938893

Menu

global purchase

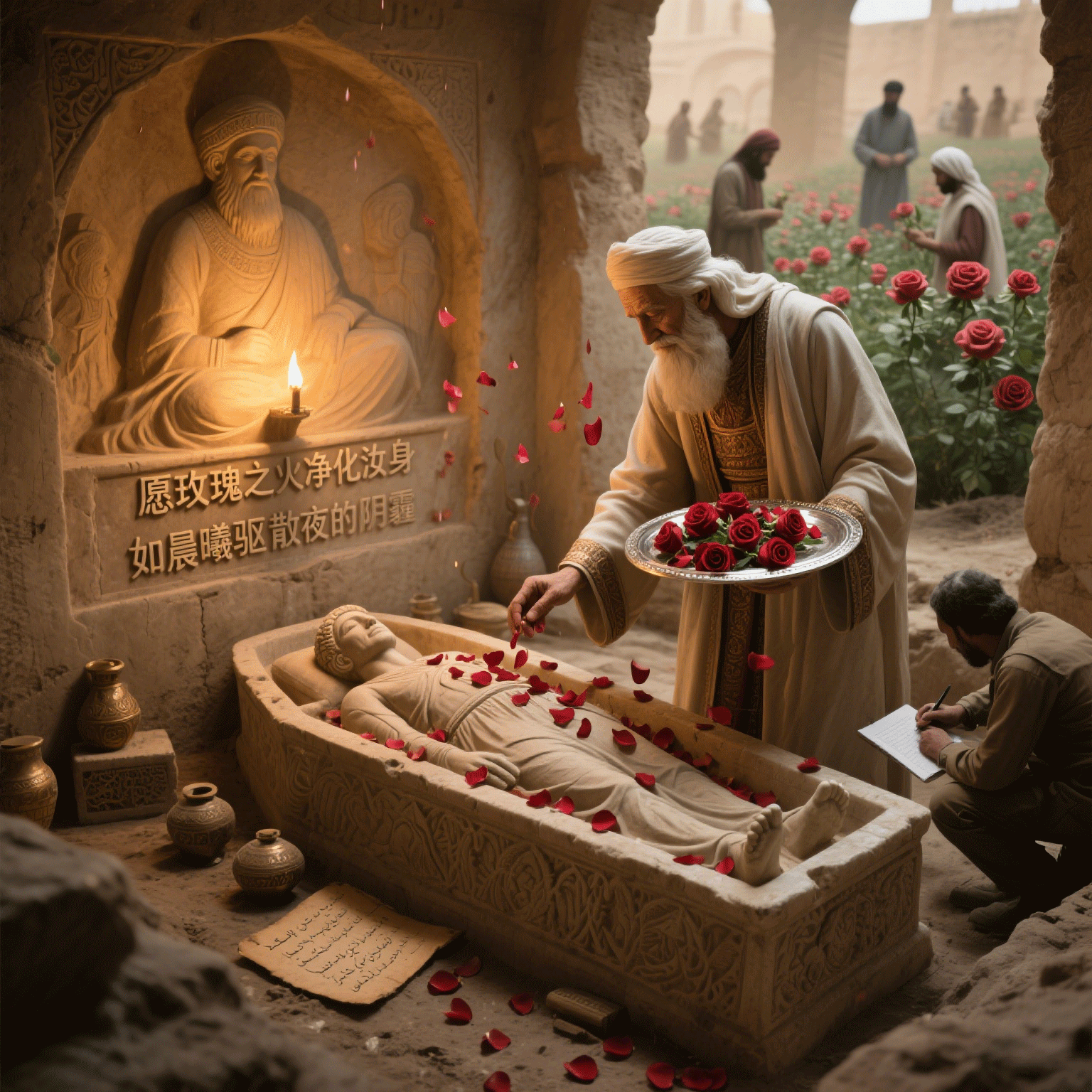

In the resplendent firmament of ancient Persian civilization, the rose perpetually served as a mystical symbol bridging the temporal and the divine. Emerging in the 6th century BCE, Zoroastrianism (also known as the Mazdayasnian religion) established its fundamental doctrine upon the dualistic opposition of good and evil. Its adherents revered fire as the embodiment of sacred radiance, while the rose's vivid crimson petals perfectly mirrored the hue of Atar - the Holy Fire in their theology. This chromatic allegory elevated the rose to a position of profound significance within Zoroastrian eschatology. When devotees departed this world, priests would lead their kin in carpeting the sepulcher with fresh rose petals - layer upon vermilion layer forming what appeared to be a blazing bed of flames. They held an unshakable conviction that the rose's fragrance and chromatic brilliance could purify the soul's impurities, guiding the deceased across the Chinvat Bridge to attain eternal serenity in the realm of Ahura Mazda, the Lord of Wisdom.

Archaeological excavations in the ancient city of Shiraz unearthed a noble tomb dating back to the 5th century BCE. The burial chamber walls bore intricate bas-reliefs vividly depicting Zoroastrian priests scattering rose petals: white-bearded elders holding silver trays, from whose fingertips cascaded a rain of crimson petals descending upon the recumbent figure in the stone sarcophagus. Accompanying clay tablets preserved this prayer: "May the fire of roses purify thee, as the dawn dispels night's shadows." This sacred equation of roses with divine fire not only imbued the flower with spiritual sanctity, but also inspired Persians to cultivate roses with exceptional reverence. When they bent to gather petals for sacred rites, their fingertips touched not merely blossoms, but a medium for communion with the divine.

Following the 7th century AD, as Islam gradually became the dominant faith in Persia, the sacred significance of roses did not fade but rather evolved into new forms within Islamic culture. Today in Isfahan's Imam Mosque, during important occasions such as Jumu'ah prayers or Eid celebrations, imams use brass sprinklers to shower rose water over the congregation in the courtyard. Within the translucent mist, the sweet fragrance of roses mingles with the aromas of frankincense and myrrh, creating a perfumed cloud beneath the majestic dome.The faithful believe this practice originates from the Prophet Muhammad's hadith describing Paradise with its "rivers of water, milk, wine, and honey, flanked by blooming roses." The sprinkling of rose water thus serves both as an earthly reenactment of the heavenly abode and as an offering of the mortal world's most exquisite fragrance to the Divine.

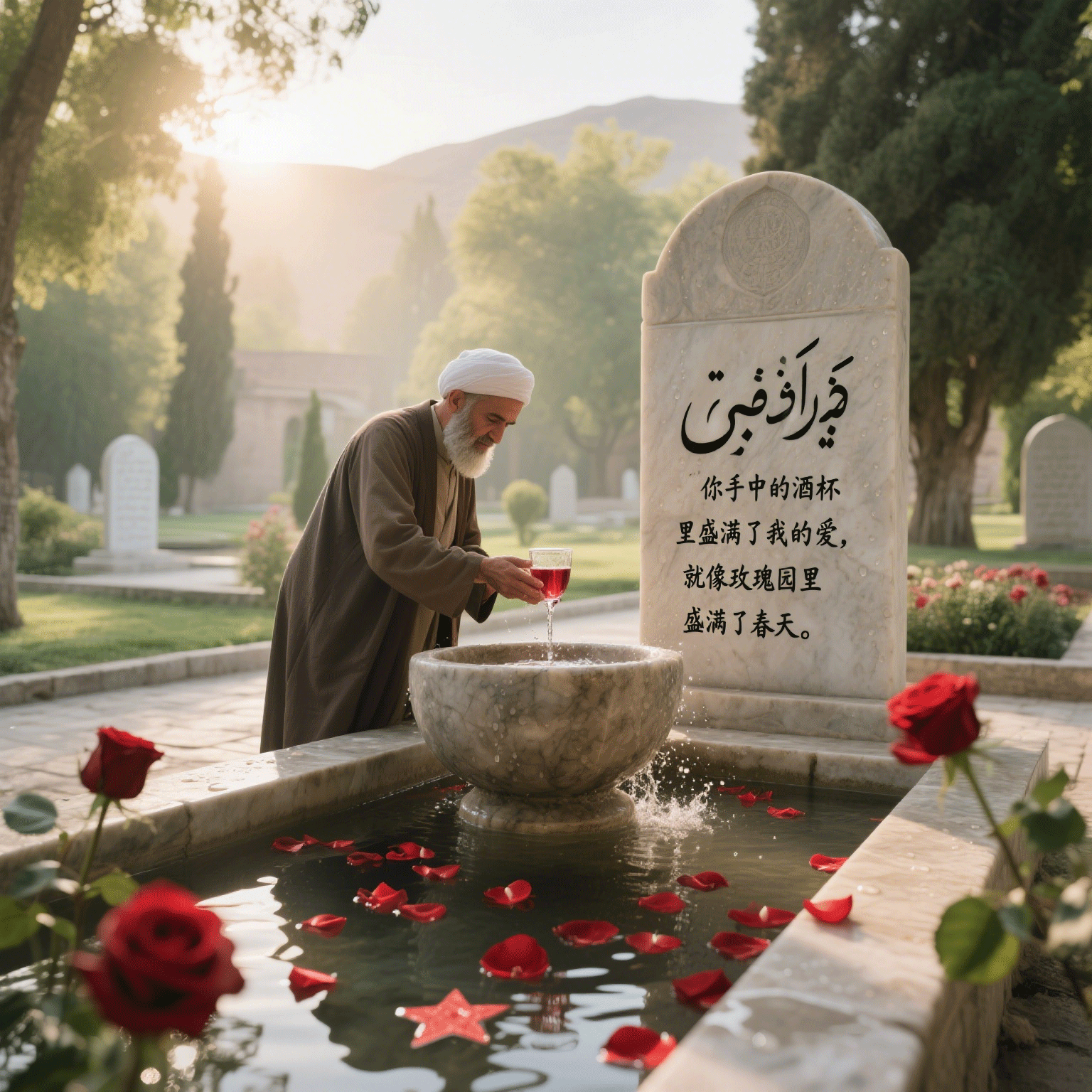

This remarkable cultural legacy spanning millennia finds its most poignant expression at the Tomb of Hafez in Shiraz: Each dawn, pilgrims fill the stone basin before the poet's grave with rose water, letting petals float like crimson constellations upon its surface. When the morning breeze stirs, droplets moisten the engraved verse on the tombstone—"Your goblet overflows with my love, as rose gardens brim with spring"—where floral fragrance and poetic cadence become one.Here manifests the quintessential Persian wisdom of weaving faith into daily life: The rose, once a sacred ritual object, has transformed into an accessible vessel of fragrance, yet continues to bear spiritual aspirations as eternal as the sacred flame that never extinguishes.