+86-13516938893

Menu

global purchase

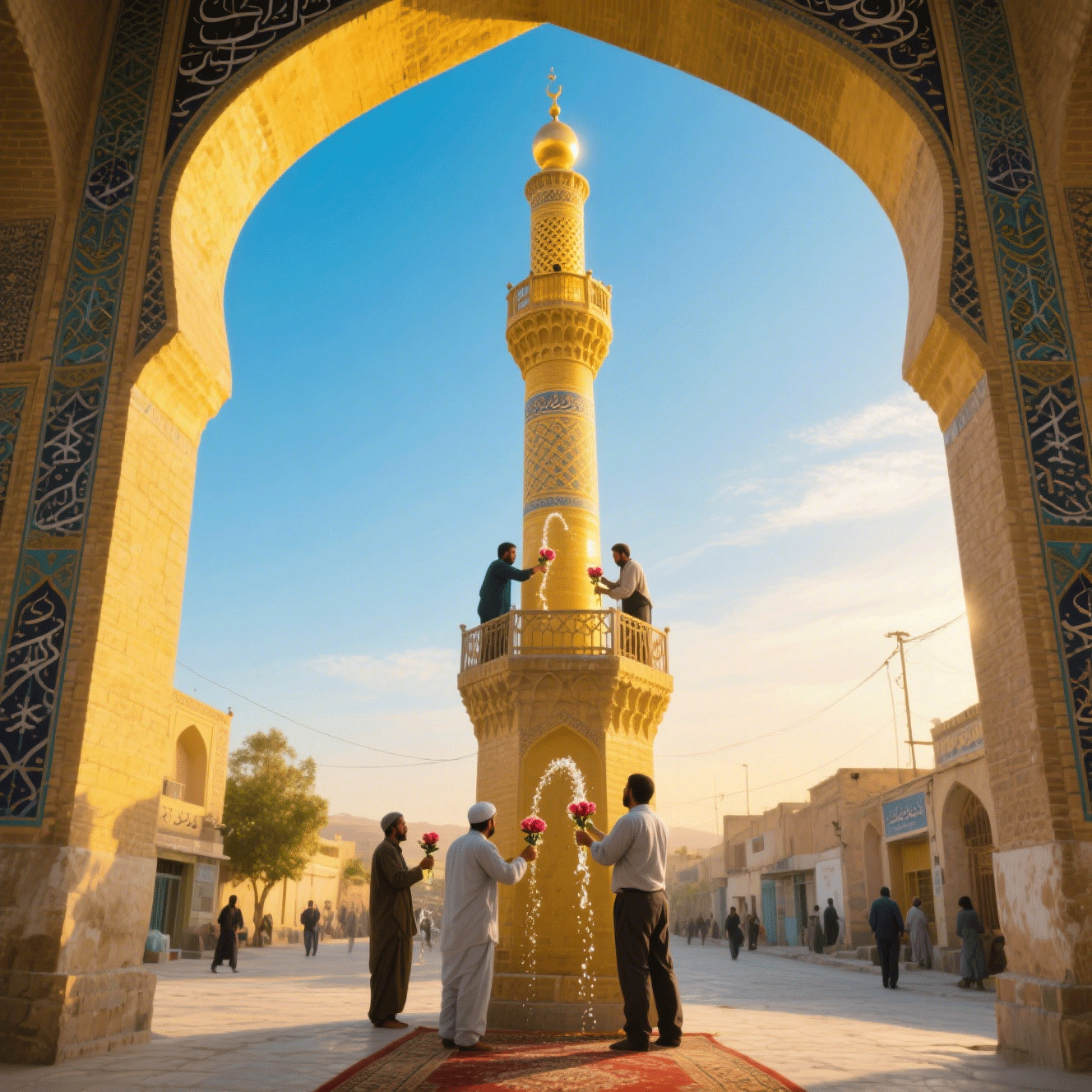

In the cultural firmament of Iran, the light of Islamic faith and the fragrance of roses have always intertwined in a harmonious dance. As the spiritual sanctuary of Shia Muslims, from the luminous shrine of Shah Cheragh in Shiraz to the holy shrine of Imam Reza in Mashhad, roses are imbued with sacred symbolism that transcends their botanical nature beneath the domes of every mosque. When the morning light filters through stained glass, casting kaleidoscopic patterns on the mihrab (the prayer niche facing Mecca) in the prayer hall, clerics gently sprinkle rosewater from copper vessels toward the direction of the Kaaba. In the delicate mist, the scent of petals blends with the aromas of frankincense and myrrh, as if cloaking the sacred space in an invisible veil of fragrance.

This tradition traces its origins to hadiths from the Islamic Golden Age: the Prophet Muhammad once caressed a red rose in the courtyard of Medina, praising its fragrance as "refreshing like the streams of Paradise, close to my breath." This story has been embroidered into Persian miniature scrolls and etched into the collective memory of Iranian Muslims. At the shrine of Fatima Masumeh in Qom, during the annual "Night of Roses" ceremony before Ramadan, hundreds of devotees carry silver rosewater flasks, circling the shrine seven times behind their religious leader while softly reciting Surah Yasin from the Quran. The holy liquid in the bottles, infused with rose essence and musk, is believed to cleanse the dust of the soul. When the last rays of moonlight graze the minaret, the faithful wipe the shrine’s railings with rosewater-soaked cloth, which is then cut into small pieces and distributed as blessed tokens.

During Ramadan, the sacred use of rosewater reaches its zenith. At Tehran’s Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, after the pre-dawn Tahajjud prayers, clerics lead young devotees in forming a "fragrance brigade," wiping every pillar and the edges of each prayer rug with rosewater. In the holy city of Mashhad, on Fridays, dozens of white-robed "rose attendants" appear among the pilgrims, shouldering giant sprinklers adorned with peacock feathers, showering rosewater mist over the crowd. Under the sunlight, the droplets shimmer like suspended crystals, reflecting the devotion of worshippers pressing their foreheads to the ground.

This tradition of treating rosewater as a "sacred purifier" has endured for fourteen centuries, remaining vibrantly alive. Today, at the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, an Ottoman-era rosewater distiller still stands beside the ancient stone basin. During major religious festivals, clerics continue to distill essential oil from the petals of the seventh-generation "Shrine Rose"—a rare variety with golden-edged petals said to have been cultivated around holy shrines since the Prophet’s time—following medieval medical texts. When the first drop of oil merges with spring water infused with agarwood, the air of the mosque seems infused with the fragrance of history, a timeless ode where faith and nature intertwine, flowing quietly through time as a testament to Iran’s eternal reverence for the divine.