+86-13516938893

Menu

global purchase

During the reign of King Manuchehr of the Persian Pishdadian Dynasty, the flames of war had raged for thirty years along the border between the Iranian Plateau and Turan in the east. The iron cavalry led by Afrasiab, King of Turan, trampled the vineyards on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea, burned down the fire temples of Zabulistan, and even tinted the snowmelt of the Alborz Mountains with the blood of soldiers. When King Manuchehr convened a council in the Golden Palace of Susa, priests gazed at the flickering flames on the sacred fire altar and declared in unison: “Only a divine arrow, offered with a life, can mark a boundary where strife will never return.”

From the shadows of the council chamber stood an archer clad in rhinoceros-hide armor. The fletching from yesterday’s battle still clung to Arash’s bowstring. His father had been a priest guarding the sacred fire, and his mother a falconer from the steppes. Since the age of seven, he had practiced archery in the Kavir Desert, capable of hitting the eye of a running antelope three li away with pinpoint accuracy. “I will be that arrow,” Arash’s voice boomed louder than a bronze bell, “so that no Persian child will ever hear the drums of war again.” King Manuchehr took his hand and saw that the calluses on his palms were heavier than the king’s crown.

On the eve of his departure, Arash went to the sacred fire altar behind the palace. The high priest dipped seven sprigs of fire-lit cypress into holy spring water, anointed Arash’s bow with the holy oil, and chanted verses from the Avesta: “The radiance of Ahura Mazda will guide your arrowhead; winds of good will shall bear your path.” Arash stroked the ox-horn bow that had accompanied him for twenty years—a bow that had once tasted the blood of an evil spirit. Years earlier, a black wolf possessed by Ahriman had attacked the fire temple, and it was Arash who had shot an arrow through the wolf’s brow. Now, he tucked a falcon feather left by his mother into his helmet; the feather glimmered silver in the moonlight.

At dawn, Arash stood atop the highest peak of the Alborz Mountains. Below him rolled a sea of clouds: to the east, Turan’s grasslands glowed green in the rising sun; to the west, Persia’s wheat fields had ripened into a golden wave. He held the bow in his left hand and drew forth a specially crafted arrow with his right—its shaft carved from a thousand-year-old poplar, its head inlaid with red-hot iron taken from the sacred fire altar, and its tail bound with colorful silks of seven hues, each contributed by the people of Persia’s seven provinces. Envoys from Turan and ministers of Persia stood on either side of the mountain, holding their breath as they watched the lone archer.

Arash took a deep breath, channeling all his strength into his arms. His bones creaked like clashing jade, and the blood coursing beneath his skin surged like the Kerman River. The moment the sun reached its zenith, he roared and pulled the bowstring to its full arc; the bow curved into a perfect crescent, and the anointed parts glowed red. With a sharp “swish” that split the air, the arrowhead—carrying the essence of his life—shot toward the sky. Arash’s body dissolved into golden dust in the sunlight, drifting away with the silks on the arrow’s tail.

The divine arrow flew for three days and three nights. On the first day, it passed over the “Eagle’s Nest” of Alamut; followers of the Old Man of the Mountain knelt in worship, believing it a miracle of Ahura Mazda. On the second day, it crossed the Kavir Desert; the sand stirred up by the arrow’s wind sprouted drought-resistant camel thorns when it fell to the ground. On the evening of the third day, as the sun was about to sink into the Caspian Sea, the arrowhead finally struck a lush walnut tree—the easternmost boundary of Turan.

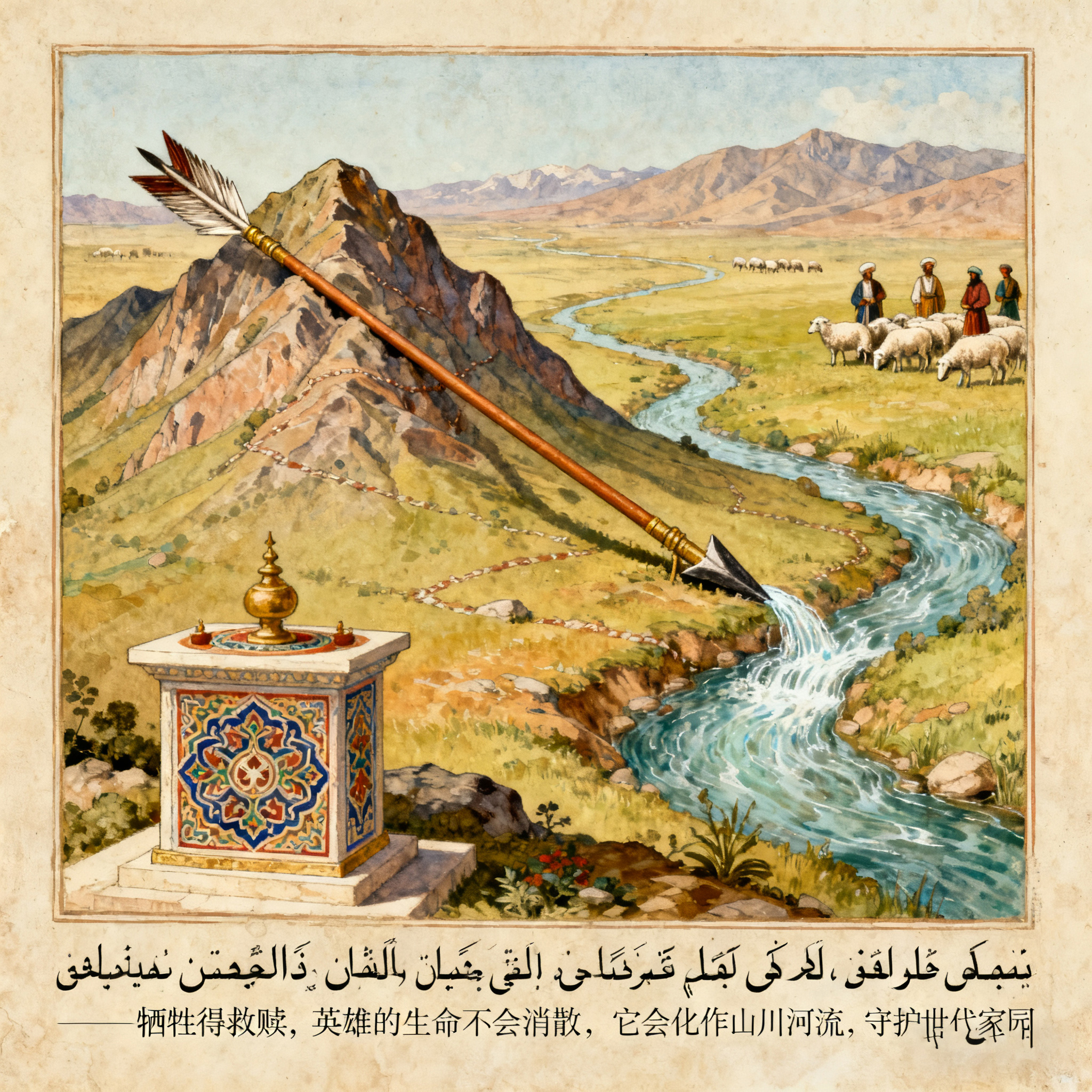

At the moment the arrow fell, a miracle occurred. Along the path from the Alborz Mountains to the walnut tree, a clear stream suddenly emerged. Dense poplar forests grew on both banks of the stream, forming a natural boundary. Afrasiab, King of Turan, witnessed this sight, broke his own spear with his hands, and knelt toward Persia: “This is the gods’ judgment, and I shall never defy it.” The Persian people built seventy-two small temples along the stream; each temple enshrined a miniature ox-horn bow.

A thousand years later, ballads of Arash still echo in Iran’s fire temples. Whenever someone asks why the river known as “Arash’s Stream” never dries up, priests point to the seven-hued silks hanging beside the sacred fire altar: “That is the hero’s life, flowing on.” In the walnut groves on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea, a piece of ancient tree stump embedded with a red-hot iron arrowhead can still be found. Herders passing by always leave a piece of naan there—a sacrifice to Arash, and a tribute to peace.

This legend weaves together Iran’s oldest heroic narratives with the Zoroastrian concept of “salvation through sacrifice.” Arash’s divine arrow not only marked a geographical boundary but also became a symbol of the Persian national spirit. As Ferdowsi wrote in the Shahnameh: “Heroes’ lives do not fade; they transform into mountains and rivers to guard their homeland for generations.”